Constellations spoke with Mike Kaplan, Vice President of Business Development at LeoStella, about the extraordinary growth driven by new smallsat capabilities, the innovation occurring between commercial and government markets, and manufacturing challenges of building to scale.

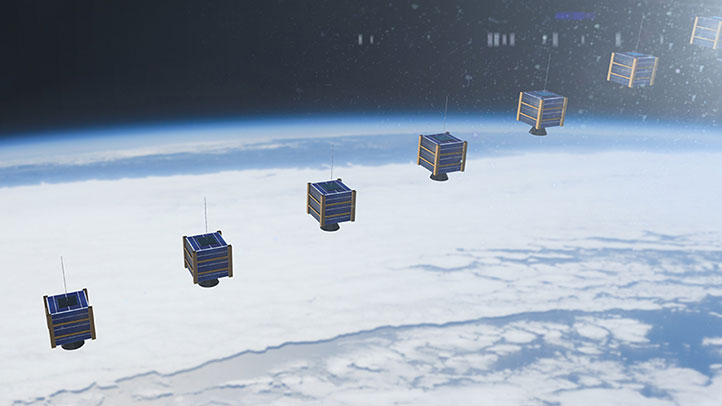

Euroconsult estimates that one ton of smallsats will be launched per day, on average, over the next 10 years, with around 18,500 smallsats launched between 2022 and 2031. According to Kaplan, this escalating demand has been driven in part by lower costs and higher capabilities that have helped close the business case.

“When you combine the forces of shrinking commercial launch costs, more capability of what you can do with small satellites and a wider variety of missions they can perform, there’s just a huge demand for small satellites across both industry and government.”

LeoStella delivers two satellites to BlackSky at New Zealand’s Rocket Lab Launch Complex 1. (Source: LeoStella)

LeoStella delivers two satellites to BlackSky at New Zealand’s Rocket Lab Launch Complex 1. (Source: LeoStella)

Much of the commercial activity has been dominated by a handful of players, like Starlink, OneWeb and others, who are continuing to build out their communication constellations. On the government side, the Space Development Agency (SDA) is charting a new path with its Transport Layer, a proliferated low-Earth orbit constellation that will consist of several hundred smallsats. Kaplan described the Transport Layer as “sort of the government version of emerging commercial systems” but with greater capabilities.

Capabilities Drive Requirements

As commercial capabilities have grown, so too has the military’s appetite for more numerous and more capable smallsats. The SDA started out with the intent to leverage existing commercial smallsat innovations, while adding specific mission requirements, like imaging, communications security functions and more advanced payloads, to meet specific military needs. Those new requirements, in turn, have fueled commercial innovation, especially as manufacturers need to develop smallsats that can support higher SWaP (size, weight and power).

Kaplan explained how a smallsat built several years ago to support 100 kilograms of payload and a couple hundred watts of power now has to support a payload on the order of 200-250 kilograms and one to two kilowatts of power.

This has led to a cycle where the government has been driving higher-end size and performance and stimulating innovation from manufacturers, which has attracted more interest from the commercial market.

“There’s this really interesting, very healthy, synergistic relationship between government and commercial customers and where it’s driven our industry,” Kaplan said, adding that commercial customers are now asking for the same requirements the government is getting.

Manufacturing Challenges

Given growing demand for smallsats, Euroconsult projects that the manufacturing market value will quadruple over the next decade to $56 billion. That has strong positive implications for those making small satellites but also raises challenges on the production side.

Kaplan identified two principal challenges for smallsat manufacturers: the first is companies shifting from building CubeSats to smallsats, the second is scale.

“Many companies start off with building CubeSats,” he said, which use a standard form factor as small as a Rubik’s Cube and can weigh as little as 1 kilogram and up to around 24 kilograms. Companies think they can make the shift easily, but going from a CubeSat to building a 300 to 400-kilogram small satellite requires a “very different” approach, Kaplan continued.

“It’s not a linear path to go from building CubeSats to building smallsats,” he said. “We’ve seen some companies struggle.”

Another challenge is going from single unit production, where the industry started, to manufacturing for a large constellation. “The choices you make in how you design [a single unit] are different than the choices you make if you’re designing a satellite that’s intended from the beginning to be manufactured at scale.”

Finding the ‘Sweet Spot’

LeoStella’s organizational structure is unique compared to other smallsat providers. The company is a joint venture between BlackSky, which is LeoStella’s primary customer, and Thales-Alenia, which helped LeoStella design its production facility for scale.

Kaplan noted that while some companies have production lines set up to support hundreds of satellites per year for one customer, LeoStella has found its “sweet spot” at a few dozen.

There are tradeoffs between the drive for scale and efficiency and a more bespoke model that can accommodate flexibility and change, he explained. A highly automated manufacturing process fits well with a cookie-cutter product to squeeze out the most efficiency and value when building hundreds of satellites a year.

But adding or changing capabilities can be difficult in a high-volume, automated production facility. Some changes can be made with block upgrades or through software. In other cases, modifications in the actual production are needed, making the case for lower production volumes and more flexibility.

“Our process is sort of a combination of very lean, hands-on and automated processes. It’s a combination of both,” Kaplan said. “So, we’re real proud of that.”

In looking ahead at the industry’s growth, Kaplan said that smallsat providers or manufacturers will have to choose to position themselves somewhere between large-scale, automated production and a more customized approach. “I don’t think you can be all things to all customers.”

As for the mission sets smallsats are being built for, some have started changing over time. There are the mainstays of communications, broadband and remote sensing. There are also emerging capabilities, like alternate PNT (positioning, navigation, and timing) as a backup for government-provided GPS systems and high-resolution ground location accuracy for applications like autonomous driving.

Kaplan also cited orbital transfer vehicles that use propulsion to move smallsats to last-mile locations in orbit. There are also growing capabilities for satellite servicing, refueling and life extension, including propellant depots or “gas stations” for orbital transfers to refuel in space to fly multiple missions.

To hear more about the evolving capabilities of smallsats, how production must adapt to growing demand, and other shifts in the market, such as the “as-a-service” model, click here.

Explore More:

The SmallSat Market’s Goldilocks Moment: Too Hot or Too Cold?

Podcast: Spiral Development, Technology Readiness Levels and Being a Constructive Disruptor

Satellite Manufacturers Adapt Supply Chains Amid Demand for Mass Production

Podcast: The Space Ecosystem, Benefits of Virtualization and Opportunities in SmallSat