WASHINGTON — Is Elon Musk living rent-free in your head? For many people in the satellite industry, the answer is yes. At least, that was the impression given by research presented by NSR, an Analysys Mason Company, at a recent event.

According to NSR CEO and Founder Chris Baugh, SpaceX and Starlink were the No. 1 issue for space and satellite executives, making up 40% of questions submitted to analysts ahead of the Satellite 2024 in Washington, D.C. It’s no surprise, either. SpaceX had another banner year. It had a record number of launches, made progress on the Starship super-heavy rocket and recently announced plans to commercialize its inter-satellite links. Meanwhile, Starlink reached 2.25 million broadband subscribers, expanded operations to 60 countries, entered new verticals and partnered with a few GEO operators.

Participants across the space value chain, already wary of Starlink, are also watching for further disruption from Amazon Kuiper, which is expected to begin service this year. The sudden shifts in the industry and influence of players like SpaceX have led to more than a few concerns about market dominance.

“Starlink and others may want a monopolistic strategy. Who doesn’t want to dominate the world, right?” joked NSR Research Director Jose Del Rosario. “But the other way of looking at it, based on events, is that maybe the competitors and incumbents who are being driven out of business aren’t competing with a value proposition that [fits].”

This was a repeated answer to several common questions about SpaceX and Starlink’s grip on the satcom market—and the emergence of Kuiper. Those who want to win in the market need to find their competitive edge in performance, pricing and even branding.

Is There Any Market Left? Yes

Currently, Starlink has over 5,000 satellites in orbit and approvals for thousands more. It is also moving aggressively beyond consumer broadband into government and mobility verticals with partnerships for maritime and in-flight connectivity (IFC) services. Even direct-to-device (D2D) service providers are hearing Starlink’s footsteps as they get closer to deploying direct-to-cell service. When complete, Starlink aims to have a constellation of 840 satellites for emergency SMS connectivity service with T-Mobile. There are real concerns among D2D first-movers that Starlink could catch up. AST SpaceMobile encountered funding challenges and delays in its planned commercial service with AT&T that have lengthened the timeframe to service. Lynk Global has also experienced delays and financial issues, which it aims to overcome after merging with a special purpose acquisition company (SPAC) earlier this year.

However, early D2D entrants may have bought some time after the U.S. Federal Communications Commission (FCC) denied SpaceX’s request to use mobile satellite spectrum (MSS) occupied by Globalstar and Dish. Moreover, as Carlos Placido, an independent satcom consultant, suggested, even if Starlink launches its full D2D constellation, it will still be short on supply for voice and data services “by a couple orders of magnitude.”

SpaceX’s expansion into new satcom verticals, like government, maritime and IFC, has left many GEO and LEO operators wondering what is left of the market. According to NSR, there’s a lot.

Roughly 75% of the global population lives above or below 35 degrees latitude, explained Baugh. “The problem with constellations today is most of them are deployed north of 35 degrees because that’s where the high-value population—market-wise—resides.” Reaching that population will not be easy for Starlink as it’s configured.

Across the globe, roughly 2.6 billion people and 400 million households are unconnected. Many of these are in those hard-to-reach markets that are traditionally best served by GEOs or small GEOs offering cost-effective, direct broadband services or satellite mobile backhaul. An executive from the Australian MNO Telstra recently emphasized how satellite connectivity is “existentially important for us in Asia,” particularly clients in rural Australia and the Pacific Islands.

Baugh noted that the market for the LEO mega-constellations “is not limitless.” In fact, network congestion in high-value target markets will likely create significant bottlenecks. In a model combining the supply of bandwidth from Starlink and Kuiper over the United States, NSR found that congestion in areas with over 100 users was a major constraint. “What’s absolutely remarkable is Starlink today and Kuiper fully deployed is about the same amount of supply over the U.S.,” Baugh said.

Becoming Revenue Positive in LEO

For years, Starlink has also raised questions about the profitability of mega-constellations in low Earth orbit. This is not only top of mind for commercial competitors, like Telesat, OneWeb, Rivada and others. It is also a concern for sovereign nations building out their own telecommunications constellations, like the European Union’s roughly 170-satellite IRIS² constellation or Taiwan’s planned LEO constellation for sovereign communications amid threats from China.

For Starlink, the road to profitability is relatively short, according to NSR models. The most optimistic estimates suggest Starlink could be profitable by the end of 2024. More conservative estimates push that date out with the low estimate projecting they will be revenue positive by 2028.

The considerations are slightly different for competing constellation operators and sovereign nations, Del Rosario explained. He noted that “if competitors are going to enter the market” they need to hit certain price points. The manufacturing cost per satellite will have to drop to roughly $750,000. Launch costs need to continue the downward trend to $1,500 per kg—which is roughly where Starlink sits. Finally, the cost to the user must be competitive.

“All this leads to the bottom line finding that the breakeven price of usable capacity—that is raw capacity—is $25 per megabit per second per month,” said Rosario, noting that premium bandwidth would need to drop to around $50 per Mbps per month.

A photograph of a slide presented by NSR, Tuesday, March 19, 2023, at an event on the sidelines of Satellite in Washington, D.C. (Source: NSR/Kratos)

A photograph of a slide presented by NSR, Tuesday, March 19, 2023, at an event on the sidelines of Satellite in Washington, D.C. (Source: NSR/Kratos)

A ‘War of Ecosystems’: Amazon vs. Google

By the end of 2024, there will be two LEO mega-constellations competing for broadband customers. Amazon’s Project Kuiper is slated to begin service by the end of 2024 and has already secured partnerships with Vodafone and Vodacom to extend 4G and 5G cellular networks in Europe and Africa.

Between new LEO capacity and next-generation high-throughput GEOs, the industry is entering a phase unlike anything it has experienced before. “We’re getting to a new environment, which is an environment of abundance,” said Placido. “Very soon, anywhere on Earth, anyone will be able to see at least 20 satellites and connect dynamically to these satellites in multi-orbits.”

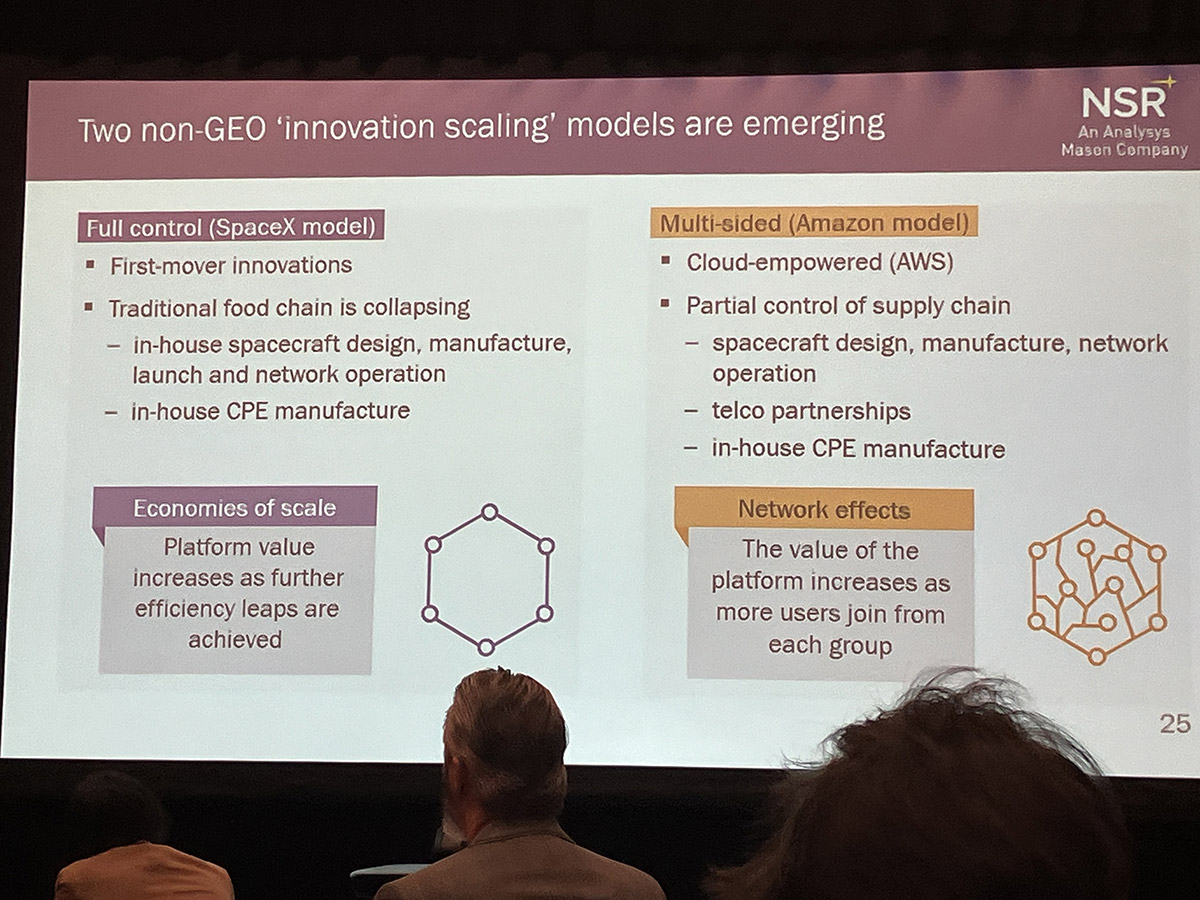

The “abundance” of NGSO capacity is largely being driven by two innovations, Placido continued. The first is the vertical integration approach taken by Starlink, with full control of the value chain from design and manufacturing of satellites and terminals all the way through launch. The other innovation is the “hyperscaler” or “multi-sided” platform approach. This approach views the satellite network as a platform to connect distinct user groups and create network effects, creating value by facilitating interactions between users. This is the approach behind Amazon and AWS’ success in terrestrial networks and is almost certain to be their approach to integrated space networks.

“Amazon will mostly likely leverage AWS to platformize Kuiper and seek those network effects,” Placido said. This would extend AWS cloud all the way to the edge and create opportunities for network virtualization, open interfaces, analytics applications, APIs and hooks to artificial intelligence (AI).

It will be interesting to see how this approach plays out for Amazon in the medium and long term and whether SpaceX is pushed into this “new game,” Placido noted. If SpaceX is forced to compete as a space-based hyperscaler, it will likely turn to its partner Google (Alphabet), which currently owns a 7.5% stake in the company.

“If we end up in a way of ecosystems, it’s likely that Google will have to jump in and have a role there,” Placido said.

Explore More

Podcast with AWS: GenAI Opportunities, Risks and Future in the Space Industry

Hughes Looks at Matchup Against Starlink Today, Amazon’s Kuiper Tomorrow

Is Kuiper a Bigger Threat than Starlink?

Commercial Satellite Players Weigh Strategy in a Future Starlink/Kuiper World