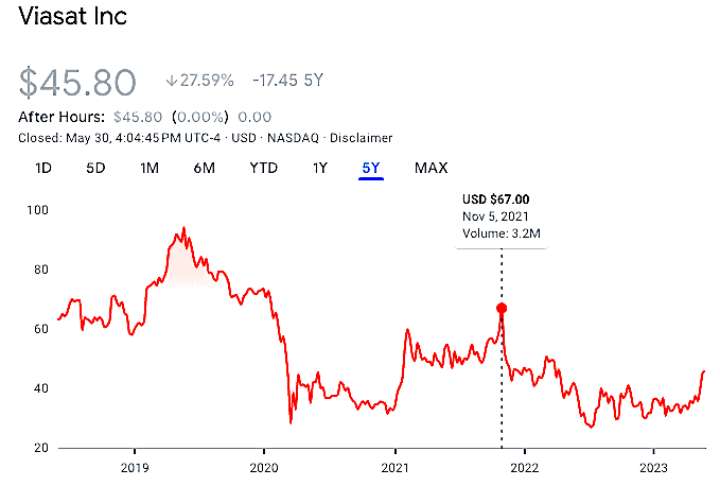

Viasat stock is down 31.6% since Nov. 5, 2021, the date at which the Inmarsat purchase was set, reducing the deal’s initial $7.3-billion valuation by about $980 million. Inmarsat’s former owners now have a 37.6% stake in the combined Viasat-Inmarsat. (Source: Google Finance)

Viasat stock is down 31.6% since Nov. 5, 2021, the date at which the Inmarsat purchase was set, reducing the deal’s initial $7.3-billion valuation by about $980 million. Inmarsat’s former owners now have a 37.6% stake in the combined Viasat-Inmarsat. (Source: Google Finance)

PARIS — Satellite broadband hardware and service provider Viasat Inc.’s purchase of London-based mobile satellite services fleet operator Inmarsat, the biggest satellite communications consolidation in 20 years, was completed May 30 after 18 months of regulatory review.

The November 2021 valuation of $7.3 billion — $815 million in cash, $3.1 billion in Viasat stock and Viasat’s assumption of $3.4 billion in Inmarsat debt — had a closing value of slightly more than $6.3 billion after accounting for the 31.6% drop in Viasat’s stock.

Inmarsat’s former shareholders hold 37.6% of Viasat’s shares.

Inmarsat officials have said the stock’s decline did not thrown into question the strategic rationale for combining fleet operators with substantial Ka- and L-band capacity and a global reach, plus Inmarsat’s S-band satellite/terrestrial aero connectivity network in Europe.

The last time the satcom sector saw a consolidation this big was the December 2001 acquisition of U.S. satellite fleet operator GE Americom by Luxembourg-based SES, valued at $5 billion, or $8 billion in today’s dollars.

Viasat assumes ownership of an Inmarsat whose financial health has sharply rebounded in the past couple of years. Inmarsat’s Q1 2023 financial report showed a company that was growing in just about all its business segments.

With the integration of Inmarsat’s asset’s, Viasat is better armed to test how a company offering near-global consumer, government and business broadband via geostationary-orbit satellites matches up against the global operators in low-Earth orbit.

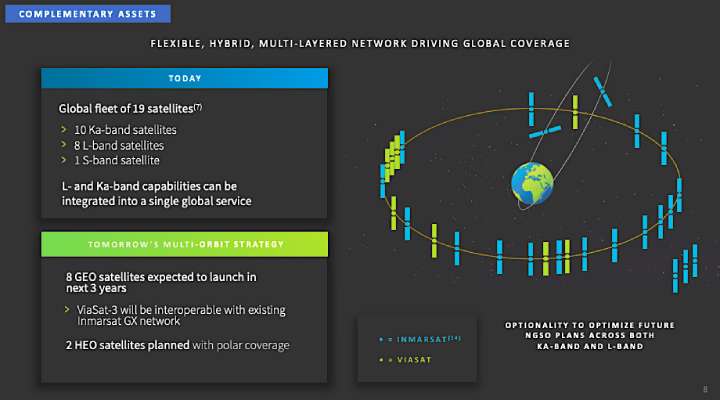

Inmarsat is in the middle of a major capex program including payloads on two satellites in highly elliptical orbit for polar coverage. Inmarsat recently purchased three small satellites to launch into geostationary orbit to back up its safety services business. (Source: Viasat)

Inmarsat is in the middle of a major capex program including payloads on two satellites in highly elliptical orbit for polar coverage. Inmarsat recently purchased three small satellites to launch into geostationary orbit to back up its safety services business. (Source: Viasat)

It’s mainly SpaceX Starlink today, but the Eutelsat-reinforced OneWeb constellation will be providing global service this year. The business case for both these constellations has not been proven, which hasn’t seemed to diminish SpaceX’s appeal to investors up to now. How indulgent Eutelsat shareholders will be is an open question.

On the heels of these two constellation is Amazon’s Kuiper, whose balance sheet is easier to track than SpaceX’s since Amazon is publicly traded.

Other constellations — including the European Commission’s Iris2, Rivada Space Networks’ government/business-targeted Ka-band network, Telesat’s Lightspeed — are in various stages of development.

These LEO networks — each costing several billion dollars — face regulatory issues, including national governments’ data-security/autonomy concerns that will favor satellite services from their own national champions.

Viasat used pre-Covid FlightAware data to assess the density of demand for in-flight connectivity. This is what resulted when the demand was multiplied by the number of passenger minutes over a week. Viasat’s conclusion: mid-ocean coverage is great, but for airlines the real need is massive bandwidh over airport hubs. Maritime is similar, with the peaks around port areas. This is the company’s argument for selective coverage in given areas, as opposed to a LEO constellation’s coverage, evenly distributed over the globe, as shown in the bottom-left image. (Source: Viasat)

Viasat used pre-Covid FlightAware data to assess the density of demand for in-flight connectivity. This is what resulted when the demand was multiplied by the number of passenger minutes over a week. Viasat’s conclusion: mid-ocean coverage is great, but for airlines the real need is massive bandwidh over airport hubs. Maritime is similar, with the peaks around port areas. This is the company’s argument for selective coverage in given areas, as opposed to a LEO constellation’s coverage, evenly distributed over the globe, as shown in the bottom-left image. (Source: Viasat)

Viasat’s argument has long been that a global broadband constellation using low-orbiting satellites is an inefficient use of capital as the spacecraft spend much of their time flying over unprofitable territories. The company reasons that whatever advantage low orbit has in offering users lower latency is overmatched by this basic flaw in the architecture.

SES’s medium-Earth-orbit O3b mPower constellation, now being fielded, is likely to expand its coverage with higher-inclination satellites and is focused on corporate and government markets. SES argues that the capex efficiencies of medium-Earth orbit compared to low Earth orbit, and the lower-than-GEO signal latency, gets the best of both designs.

On a regional level, multiple smaller operators of geostationary-orbit satellites are plotting how to use government support for universal broadband service provision to establish a bulwark against the global fleets.

China is presumed to be outside the reach of a non-Chinese satellite fleet providing consumer broadband. But aeronautical connectivity — a key market for Viasat — is a different matter.

India’s market is opening, and OneWeb’s partnership with India’s Bharti Global should give it an advantage. But it’s still not clear whether India’s ever-busy regulators will open India’s full potential as a market for satellite broadband providers.

Viasat has said its answer to the market uncertainty is a geostationary satellite business model that does not need to reach every geography, but can train large capacity into those markets and high-demand regions that are open. Aero mobility, maritime and government users are the key.

On the consumer side, Viasat’s new Viasat-3 satellites offering global coverage outside the poles may not need much of a consumer business. If they can demonstrate their value in high-demand markets, that may be enough.

In a May 31 statement, Viasat confirmed that its new “global international business” will be based in London, while the company’s headquarters will remain in Carlsbad, Calif.

Viasat and Inmarsat took pains to present the transaction as a win for Britain in terms of future investment.

Britain’s minister of Science, Innovation and Technology, George Freeman, issued the following statement on May 31:

“Satellite communications is a hugely significant and strategic global market for the U.K. space sector, now poised for an exciting next phase. The combination of Viasat and Inmarsat creates a global leader in satellite communications here in the U.K. It brings significant investment, hundreds of new highly skilled jobs and will serve as a catalyst for substantial economic growth.

“Having met both companies, I look forward to working with them as we use the U.K.’s regulatory freedom and leadership to support advanced technologies to boost the space economy’s productivity, profitability and sustainability,” Freeman said.

Read more from Space Intel Report.