Dennis Burnett, executive VP and general counsel, Hawkeye 360. (Source: Hawkeye 360)

Dennis Burnett, executive VP and general counsel, Hawkeye 360. (Source: Hawkeye 360)

MOUNTAIN VIEW, California — It’s often said government cannot keep up with private-sector technology advances. But when it comes to restricting exports, it’s a different story.

Satellite technologies that were once the exclusive province of governments but now are creating new commercial markets risk being labeled as military and relegated to the U.S. Munitions List.

The outpouring of NewSpace companies in recent years has created these new markets, and most of them are internationally competitive. So it is that the satellite industry’s most-notorious four-letter word, ITAR, is back on the agenda.

Export reform is a never-ending process, not a destination. (Source: US Department of Commerce)

Export reform is a never-ending process, not a destination. (Source: US Department of Commerce)

It sounds like a repeat of a decade ago, and it is. The difference now is the speed at which new commercial applications are being found, especially in Earth observation.

Signals intelligence, or monitoring radio-frequency emissions from low Earth orbit, is now following the path of high-resolution optical imagery in the 1980s and 1990s and synthetic-aperture radar (SAR) images in the past decade.

Here’s the sequence.

Phase 1: A newly viable commercial technology that resembles what governments have been using for years is restricted to prevent its spread to adversaries.

Phase 2: Companies in allied nations adopt their own versions of the technology and a competitive market is born. U.S. companies can take part in this market, but only after navigating the complicated, and expensive — Cue the legal teams — process of getting U.S. State Department approval, customer by customer.

During this period, non-U.S. competitors warn customers that ITAR and the less-onerous U.S. Commerce Department Export Administration Regulations (EAR) are fearsome beasts that are best avoided.

Phase 3: At some point, the reality of an international, competitive market becomes clear to the relevant U.S. government bureaucracies, and the restrictions are eased, leveling the playing field and freeing startups from near-total reliance on the U.S. government as a customer.

U.S.-based Hawkeye 360 was formed in 2015 and launched its first spacecraft in December 2018. That was Phase 1.

In August 2019, Unseenlabs of France launched its first SignInt satellite, and in November 2020, Kleos Space of Luxembourg launched its first demonstration mission. Phase 2 began.

Given the potential of commercial SigInt — exposing illegal fishing alone should be a large market — more companies are sure to follow.

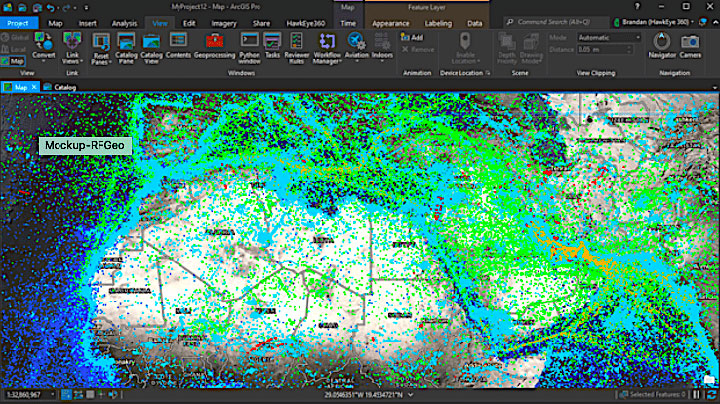

(Source: Hawkeye 360)

(Source: Hawkeye 360)

Dennis Burnett is Hawkeye 360’s chief counsel and a veteran of the ITAR wars that were settled, at least for communications satellites — the restrictions were never eased for launch vehicles — in late 2014.

Burnett discussed where Hawkeye’s products now sit in the U.S. regulatory regime.

What regulatory approval does Hawkeye need before selling its data to a non-U.S. customer?

When we provide the data products that we derive from our satellites to a foreign party for export, it is a “defense service.” We fought it [at the U.S. State Department] and we lost. They decide, based on national security and foreign policy, what’s to be included in the USML [U.S. Munitions List] and what’s not.

That means, essentially, that when we need to export any our data products to a foreign policy, we need to get either a DSP-5 [a license to export items not returning to the United States] for marketing purposes, or TAAs, Technical Assistance Agreements, for launches and contracts.

We have submitted more than 100 applications for authorizations, and we have received around 85 or so, with another 15 in progress.

Every request has been granted. Yes, it takes some additional time. They don’t work at the speed of business, so we have to adjust our timelines.

That is obviously a disadvantage for us.

On the other hand, the fact that they are approving it shows that what we’re providing has national security and policy importance to the US government. It is also valuable to foreign governments.

We have been very careful to conduct ourselves in an ethical way. We won’t sell to any country that’s under UN or US embargo. We follow OFAC [Office of Foreign Assets Control] very carefully, we follow all the requirements of EAR and ITAR. And we would do that no matter what.

Is having to secure TAAs is a headwind in a competitive environment?

It is. The parties in the U.S. government are very aware of this and aware of what happened with electro-optical imagery. The delays encountered there in getting national security clearance for changes in resolution and other issues really hurt electro optical, and particularly SAR [radar satellite imagery].

I have had several people in the government tell me: We don’t want to repeat that. And they are moving very quickly to accommodate what we need to do in order to compete.

How much of a struggle will it be to get the TAA requirement lifted?

We’ve done around 100 in a little over a year. Fortunately I’ve got a lot of experience in this and I’ve got a staff that is really good at this. We’ve got experts and we’re handling it that way, and they are treating us accordingly. I cannot complain about they way they have handled our licenses — not one bad word.

This is exactly the same debate from the early 2000s, which led to ITAR reform on the satellite side, if not on the launcher side.

This is the argument we have made to the State Department, that they ought to make a distinction between information that relates to purely commercial signals and information that relates to intelligence or military communications. They don’t want to go there — yet.

I think it’ll happen but they need to get comfortable with it. They need to understand all the ramifications for national security if they allow purely commercial products to be classed under EAR instead of ITAR. It’s going to take some time.

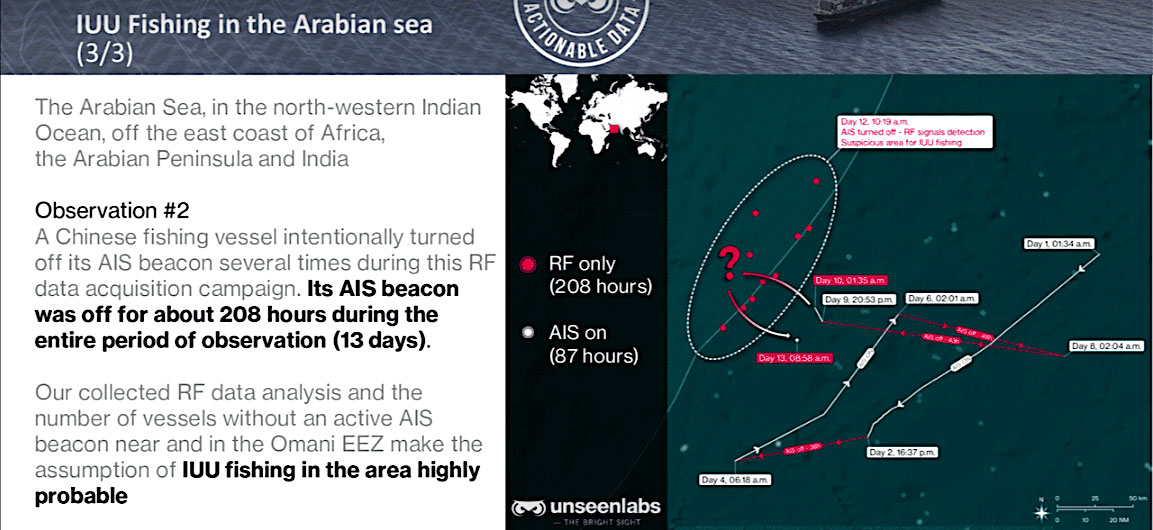

(Source: Unseenlabs)

(Source: Unseenlabs)

So the State Dept. will need to see non-U.S. commercial SigInt companies making inroads in the market?

That will be part of it. But it will take changing the way the government works. It’s the same issue we had, frankly, going back to 1980 — a long time ago — when we were commercializing remote sensing. People in the government who were doing that as a purely government function had trouble coming to terms with the idea that a commercial entity would be doing what they had been doing.

Then France arrived in the mid-1980s with Spot Image to make a commercial business out of this.

Exactly. So we’re talking about the same sort of issue involving people and roles and missions. At least we have people in the government who understand the history of it, and understand that it can’t be done the way it was done before.

There’s enough institutional memory at State to inform the discussions on this, and not just people whose regulatory experience is too recent to know what you’re talking about?

Absolutely. They may not be my age — but they still know!

Just to be clear: The issue is with the datasets Hawkeye is producing to sell to customers, not how you are producing them. It’s the product that’s the issue.

It really is the product. They consider that giving to a foreign person the information in the product is a defense service. I won’t go into how they got there, because it’s very complicated. But that’s the end result.

As with optical and radar imagery, this might be a reasonable decision at one point. Then some other company produces it and becomes competitive, and it’s no longer a reasonable decision.

The further complication is that industry keeps improving and the capabilities keep improving. And that’s happening while they’re assessing the situation. This is a business time frame. Each new constellation is going to have some sort of improvement in it. That’s the only way we can compete.

And for the moment, what we can do is way beyond what the competitors can do.

I’m sure there will be a debate on that. Hawkeye was first to market. Once the others reach cruising speed with their constellations it will be easier to compare.

It is really interesting how this has evolved since the reform that occurred during the Obama administration and what’s taken place since then, a bureaucratic resistance to that.

That was no easy task for industry to get those reforms in 2014. It took years.

It was immense. It really was.

Read more from Space Intel Report.