ALEXANDRIA, Va. — In late July, U.S. Space Systems Command (SSC) released a draft framework for the Commercial Augmentation Space Reserve (CASR), a military-commercial partnership whereby the Department of Defense could call upon the private space industry capabilities during times of conflict or crisis.

In this file image, senior material leader for the Commercial Space Office Col. Richard Kniseley addresses an audience at the grand opening of the COSMIC facility in Chantilly, Va. on June 6, 2023. (Source: U.S. Air Force/Cherie Cullen)

In this file image, senior material leader for the Commercial Space Office Col. Richard Kniseley addresses an audience at the grand opening of the COSMIC facility in Chantilly, Va. on June 6, 2023. (Source: U.S. Air Force/Cherie Cullen)

On August 1-2, SSC invited members of industry to discuss the draft framework in a series of review sessions hosted by the Commercial Space Office (COMSO) at their new headquarters in Northern Virginia. According to people who attended Day 1 sessions, industry feedback was focused on clarifying how their involvement in the program would impact them operationally, legally and financially. Some of the most robust engagement revolved around vendor requirements, cybersecurity and understanding the tangible benefits of agreeing to turn over commercial capabilities to the government in a time of acute need.

To accommodate more feedback, SSC extended the CASR request for information (RFI) through Sunday, Aug. 20. SSC also said it would accept longer submissions and attachments relevant to the questions outlined in the RFI template.

Borrowing from the Civil Reserve Air Fleet

The concept of CASR was inspired by the Civil Reserve Air Fleet (CRAF), often considered one of DoD’s most successful public-private partnerships. Following the Berlin Airlift, the Truman administration began work to allow the Air Force to contract with commercial carriers to augment airlift requirements during emergencies. Under the program, commercial airlines voluntarily contract with the military to cover different levels of contingencies, from minor crises or disaster relief to theater war up to a major national mobilization. Carriers agree to dedicate a portion of their fleet, as well as personnel and facilities, to DoD during different levels of contingencies in exchange for incentives, such as regular paid flights during peacetime and predetermined rates for conflict. Carriers are guaranteed regular business and the military saves billions of dollars by not purchasing or maintaining a large fleet of dedicated airlifters.

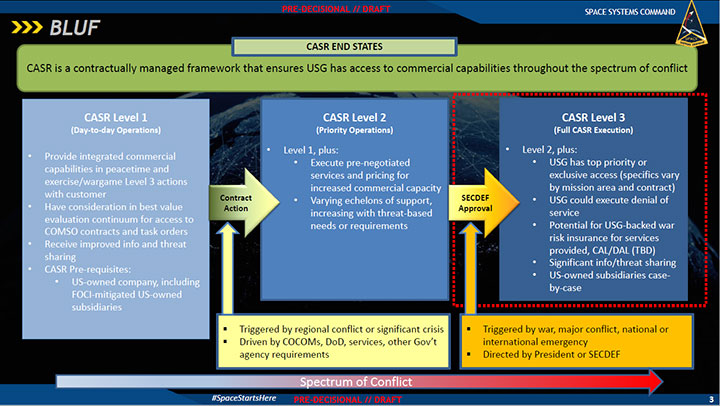

Like CRAF, the idea behind CASR is to have a “contractually managed framework” for space companies to voluntarily support DoD throughout the spectrum of conflict—from peacetime operations (Level 1) to regional conflicts or crises (Level 2) up to war (Level 3). Throughout the spectrum, companies maintain and operate their systems as civil systems under government direction.

Level 1 represents an entry point for companies to test, validate and onboard capabilities through activities like wargames, technical integration, training, ops and maintenance. This level establishes a baseline to ensure commercial capabilities are ready to be utilized by the warfighter and interoperable with existing programs. By Level 2, contracts would be in place to enable U.S. Space Command and Space Force to draw from a pre-negotiated surge capacity, maintained by the company for contingencies. At this level, the company should be able to assist the government without interrupting regular commercial services or operations. At Level 3, the government would have priority or exclusive access to capabilities—depending on the contract specifications. At this level, described euphemistically as “a very bad day,” companies, their customers and shareholders should expect disruptions to commercial operations or services. They may also deny service to some customers according to national security needs.

Levels of operation described in the draft CASR framework, released publicly on SAM.gov, July 24, 2023. (Source: SSC/SAM.gov)

Levels of operation described in the draft CASR framework, released publicly on SAM.gov, July 24, 2023. (Source: SSC/SAM.gov)

Unlike CRAF, which covers a narrow mission set, CASR is looking to acquire and integrate a broad array of commercial space capabilities. This variety was reflected in the invitations to the feedback sessions, where SSC solicited input from companies involved in satcom, data transport, position, navigation and timing, remote sensing, space domain awareness (SDA), command and control, ground systems, cloud, space mobility and logistics, tactically responsive space and launch.

Understanding CASR Requirements

Ultimately, SSC is looking for mature capabilities that are ready to be integrated immediately, rather than technologies that are still being developed. At the same time, the space acquisition command also wants to be able to leverage the latest innovations. According to the draft framework, Space Command and Space Force plan to “develop minimum requirements” for CASR companies during peacetime. Companies will be expected to meet a “minimum commitment of capability” and will be assessed and monitored for compliance based on the metrics developed.

For companies to participate in any CASR level, they will be expected to achieve and maintain the desired capabilities for the duration of their contract. They will be evaluated for risk factors, like operational and financial health, supply chain vulnerabilities and IT security, to name a few. The framework elements also indicate several other conditions companies will have to meet to be considered for CASR. This raised questions among numerous industry participants about the costs of contributing to the program and how those would be offset by adequate benefits.

For example, one framework element referred to requisite “thresholds” commercial vendors would need to meet to establish interoperability and integration. Vendor capabilities would need to be tested and evaluated for performance, reliability, compatibility, security and the like. In this case, officials acknowledged explicitly that CASR requirements “may drive cost.”

In the area of cybersecurity, the framework highlighted compliance with NIST 800-53 standards and the Risk Management Framework’s seven-step process. However, it was unclear to those attending the event whether that was the extent of the requirements. Industry participants were eager to understand what controls they would have to implement, whether they would apply enterprise-wide or be program specific, how compliance would be verified and at least one question about IA-Pre for COMSATCOM providers. Officials noted throughout the listening sessions that the CASR framework represented a draft and additional details would be elaborated in future documents or addressed in contracts on a case-by-case basis.

Incentives, Benefits and Dedicated Budgets

Officials welcomed industry participation at all levels of CASR and briefly sketched the incentives or benefits participating companies might receive. Depending on the level of participation and contract specifics, a vendor could expect to receive classified threat briefings, wargaming and priority access to DoD exercises, as well as data-sharing and analytics. Officials also floated the idea of a CASR certification and accreditation program that could help bolster a company’s credibility.

The draft CASR framework also touched on the idea of “preferential” access to national security space contracts and tasks orders as well as a “payment structure of compensation” for a company to maintain the readiness levels needed in a conflict. Additionally, SSC suggested it might enlist the support of private investors or establish funding mechanisms to support technology integration, testing, training and deployment of relevant technologies.

Several questions came up about whether a payment structure would resemble a “retainer” and, essentially, whether the incentives would translate into real money. Officials were also pressed to elaborate on what it might look like to be given “preferential” access to contracts or task order. Given the current level of involvement most commercial space companies have with DoD, there were questions about how CASR membership would be a meaningful differentiator. Finally, some participants felt there was ambiguity about how Federal Acquisition Regulation (FAR) concepts, like “best value evaluation,” would be applied in the context of companies qualifying for preferential considerations under CASR.

Of course, all the potential benefits to industry participants and the benefits to the government of a commercial space reserve will rely on funding that has not been secured yet. SSC is working actively to secure “consistent funding” for CASR in the FYDP (future years defense planning). This appears to be part of the ongoing effort to establish a dedicated budget for commercial space. The Commercial Space Office is currently engaged with Congress and could potentially have a commercial space budget line funded by the FY 2025 budget at the earliest. Additionally, SSC is exploring options for other combatant commands or agencies to move contingency funds to quickly execute CASR contracts.

One area where SSC officials were able to offer some clarity was around legal liability. While the draft proposal certainly raised legal questions for organizations to answer, it also offered war risk insurance as a legal backstop for companies whose activities with DoD would not be covered under traditional commercial insurance. SSC officials also appeared to dismiss the idea of indemnification for space companies who put their assets in harm’s way, despite months of public discussion of the idea. The task force behind the CASR framework determined indemnification was not appropriate outside a small set of cases and that war risk insurance was preferable.

The Steps Forward

SSC representatives repeatedly emphasized that the draft framework was “pre-decisional” and that officials would weigh industry feedback as they move forward. After reviewing the RFIs, SSC officials will brief senior Space Force leaders. The final CASR framework will need approval from SSC, Space Force senior leadership and the Secretary of Defense, who is the designated authority to trigger a Level 3 activation—along with the President of the United States. In the near future, SSC is planning to engage with commercial providers further with reverse industry days and other avenues to explore capabilities and potential contracts.

Officials said they were confident a CASR framework could be enacted on a faster timeline than the roughly eight years it took between the establishment of CRAF and its first commercial contract. There are clearly several areas to work through and clarify with industry stakeholders before Space Force can boast a reliable, active commercial space reserve. The considerations are complex, the capabilities being sought after are diverse and companies are demonstrating new, innovative capabilities rapidly. The CASR program is in its very early stages and will be shaped by the feedback and questions industry provides.

Explore More:

Will SSC’s New Commercial Space Office Help Innovators Bridge ‘Valleys of Death’?

Podcast: Intentional Collaboration, Asking the Right Questions and Turning the Ship Around

Space Systems Command Talks about Opening the ‘Front Door’ to Industry Innovation