Originally published by Space Intel Report on March 31, 2025. Read the original article here.

Astroscale’s 2nd-generation docking plates. (Source: Astroscale)

Astroscale’s 2nd-generation docking plates. (Source: Astroscale)

LA PLATA, Maryland — Three companies that have made concrete investments in satellite in-orbit servicing — Airbus Defence and Space, Astroscale and Intelsat — outlined what it will take for the business to reach commercial viability and why Intelsat’s pioneering satellite life-extension missions with Northrop Grumman in geostationary orbit were not enough to catalyze market uptake.

In a webcast organized by the Global Satellite Operators Assn., GSOA, the three companies said the market is waiting for much more buy-in from government agencies before making a commitment.

Andrew Faiola. (Source: Astroscale)

Andrew Faiola. (Source: Astroscale)

“The role of government is important to establish the regulatory framework and to be that first customer,” said Andrew Faiola, commercial director of Astroscale UK, which along with its sister company in Japan is all-in on the future of in-orbit servicing and manufacturing (ISAM).

“We are not looking for handouts. We are looking to validate the technology we are developing. In many case it’s the government who can help that. The commercial operator is more conservative and wants to see it work first. The key to bringing down the cost is going to be doing this again and again and government in the early days can really help make that happen,” Faiola said.

Satellite life extension and refueling has been seen as the most likely on ramp for commercial ISAM. But life extension is not an obvious choice for satellite constellation operators, whose satellites have shorter service lives and much lower per-satellite value than GEO-orbit satellites.

Astroscale is looking at LEO as a market for its docking plates to allow them to be more easily grappled by services and then brought down to lower orbit for disposal.

Airbus order for 100 Astroscale docking plates, a commercial milestone

Airbus, which is building 100 additional Gen 1 OneWeb broadband satellites for EutelsatGrouop, recently contracted with Astroscale for 100 second-generation docking plates. It was a milestone contract for the industry.

OneWeb satellites orbit at 1,200 kilometers in altitude, too high to decay within a reasonable period, so they will need to be actively deorbited, one by one, to meet current US and likely future European regulations.

Simon Rose. (Source: LinkedIn)

Simon Rose. (Source: LinkedIn)

Simon Rose, head of tech strategy & R&D at Airbus Defence and Space UK, said the lack of standardization is a headwind for commercialization of ISAM.

“The market isn’t big enough for 4-5-6 different solutions to refueling and grasping spacecraft,” Rose said. “Key will be collaboration for standards of interfaces and latching on.”

Rose agreed that LEO satellite constellations are likely not a prime market for life-extension/refueling missions, but he said tomorrow’s refueling technologies may find a large commercial customer set.

“Today we fuel to 100% at launch to get the maximum satellite lifetime,” Rose said. A refueling mission could permit satellite operators to fuel only to 50% at launch, which would lower launch cost or enable the use of smaller rockets.

“If there’s regular refueling in orbit, then fuel mass isn’t so critical. And modularity to enable uploading payloads during a mission, or sell a satellite at the end of life, could open up a second-hand market for spacecraft.” But Rose also stressed the government role in carrying the technology from demo to commercial operation.

Intelsat’s decision to hire Northrop Grumman’s SpaceLogistics division to launch two large mission-extension vehicles to attach to two aging but otherwise healthy satellites made headlines the world over. Both were successful. But Intelsat and Northrop are not typical actors.

Jean-Luc Froeliger. (Source: Space Data Assn.)

Jean-Luc Froeliger. (Source: Space Data Assn.)

“Northrop Grumman has a lot of technical and financial depth, with R&D money to spend,” said Jean-Luc Froeliger, Intelsat senior vice president for space systems. “What we see nowadays is a lot of startups. I can name 12 different startups, most in the US but some also in Europe, that are into the life-extension business. Some already have contracts with us, some with the US government.”

The US Defense Innovation Unit and the US Space Force are both financing demonstrations of in-orbit servicing with companies including Astroscale and SpaceForge as well as Northrop Grumman. In Europe, the 23-nation European Space Agency (ESA) in October 2024 contracted with D-Orbit to design a vehicle capable of docking with a GEO-orbit satellite to extend its life.

Once this catches on, Froeliger said, it will be much easier for startups to raise venture capital money.

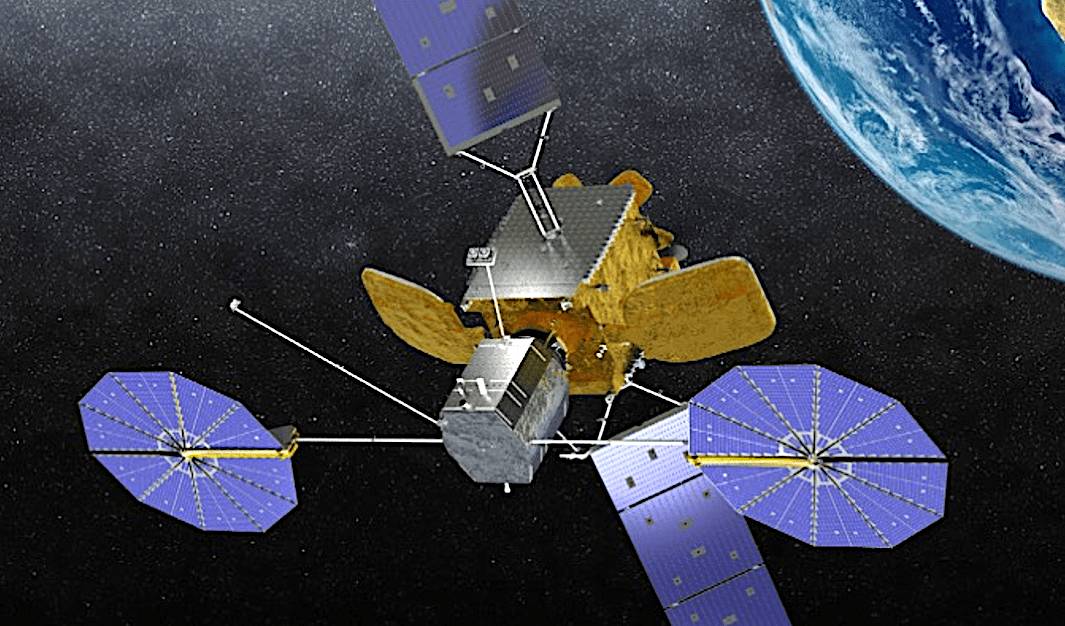

Intelsat was the inaugural customer for Northrop Grumman’s Mission Extension Vehicle. Five years on, it remains one of a kind. (Source: Intelsat)

Intelsat was the inaugural customer for Northrop Grumman’s Mission Extension Vehicle. Five years on, it remains one of a kind. (Source: Intelsat)

Intelsat’s experience with the Northrop Grumman mission-extension vehicles was positive and cost-effective for Intelsat to order the much smaller Northrop Mission Extension Pods for future life-extension missions.

Here’s Froeliger’s summary of why this works for Intelsat, and why this success cannot be extrapolated to the industry at large.

“The first life extension we did was with Intelsat 901, a satellite designed for 13 years,” Froeliger said. “With life extension, which ending in the coming weeks, we will have 24 years of life of that satellite. We were able to make the business case work because the cost of life extension was good enough given the revenue from our customers. We were the first mover and I would not say it’s sustainable long term. It all depends on the revenue you are making on the satellite.”

Intelsat’s fleet used to be primarily for television broadcasting, when customers would sign on for satellite capacity for the full life of the satellite.

With the contraction of the satellite sector, these customers are now committing for five years, sometimes less.

“So for us it makes sense to extend the life of a satellite for 4-5 years because it’s cheaper than buying a replacement satellite that will last 15 years when you don’t know if the customer is going to be there after five years,” Froeliger said.

Aside from satellite fleet operators facing the same customer set, Froeliger said the big life-extension market may need “very large, expensive geostationary satellites, primarily government, maybe classified, that cost hundreds of millions,” Froeliger said.

“And then there are us commercial operators that can use of on a case-by-case basis.”

The discussion did not address whether the advent of all-electric satellites will reduce the need for in-orbit life extension.

Mike Curtis-Rouse. (Source: Satellite Applications Catapult)

Mike Curtis-Rouse. (Source: Satellite Applications Catapult)

Whatever the market size, it will take government push, said Mike Curtis-Rouse, head of ISAM at Britain’s Satellite Applications Catapult.

“We need to see platforms be facilitated [with] some form of state-based intervention, either a multinational agency like ESA, or individual space agencies,” Curtis-Rouse said. “The ability to do docking and rendezvous with spacecraft provided by a third party to use as a test and validation platform. It could have a payload but the main activity would be as a docking platform for services including refueling or topping up batteries. We need a series of orbital demonstrators to facilitate it.”

Originally published by Space Intel Report on March 31, 2025. Read the original article here.