ALEXANDRIA, Va. — Events of the past year highlighted the importance of maintaining a peaceful, stable space operating environment as a greater number of military, civil and commercial space operators affirmed or challenged norms of behavior.

This 2022 year in review looks back at the most consequential developments in space governance.

- UN Approval of ASAT Test Ban Resolution

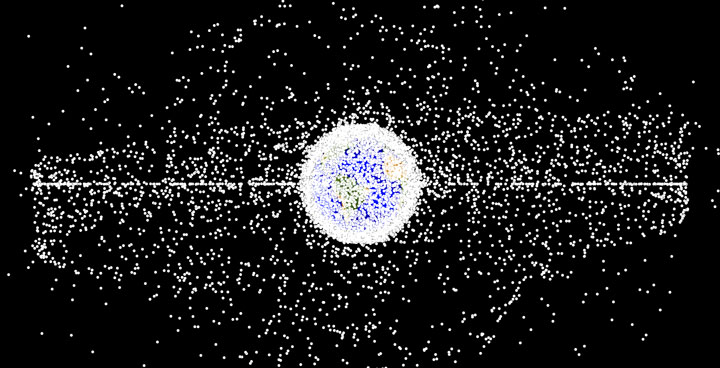

ASAT tests in recent years have created thousands of pieces of trackable debris. The U.S. and other nations introduced a U.N. resolution to promote a moratorium on these destructive tests. (Source: NASA)

ASAT tests in recent years have created thousands of pieces of trackable debris. The U.S. and other nations introduced a U.N. resolution to promote a moratorium on these destructive tests. (Source: NASA)

The UN General Assembly’s overwhelming approval of a resolution to halt testing of destructive direct-ascent ASAT weapons was a significant accomplishment for nations seeking to build norms of behavior to preserve space as a stable operating environment. An overwhelming 155 nations voted Dec. 7 in favor of the resolution, which was first introduced by the United States. Nine nations opposed the test ban, including China, Russia and Iran. India and eight others abstained. To date, China, India, Russia and the United States are the only nations that have conducted destructive ASAT weapons tests, which have created tens of thousands of pieces of orbital debris.

The UN resolution is voluntary, nonbinding and largely symbolic but it shows progress in elevating the international discussion from restrictive debates about space weapons to government behaviors that impact the space operating environment. “To go from this not being discussed at the international level two years ago to having overwhelming support is significant,” said Secure World Foundation Director of Program Planning Brian Weeden. “It’s an important first step if we ever want to get to a legal ASAT test ban treaty.”

There are hopes that further progress will be made toward international space norms and principles by the UN Open-Ended Working Group on Space Threats. The working group, created at the end of 2021, was the impetus behind the ASAT test ban resolution. It is scheduled to hold its first 2023 meeting Jan. 30 – Feb. 3.

- FCC’s 5-Year Deorbit Rule

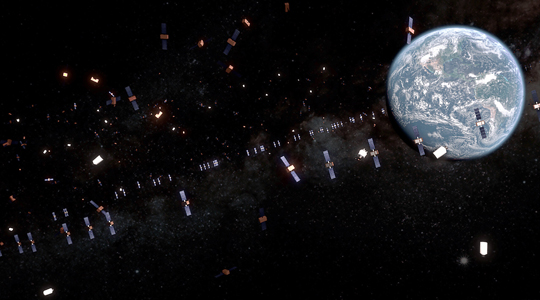

With commercial operators planning to launch more than 10,000 satellites over the next decade, the U.S. Federal Communications Commission (FCC) finalized a rule in September requiring LEO satellites (orbiting below 2,000 km) to deorbit no later than five years after completing their missions.

The U.S. FCC established a final rule for LEO satellites in large constellations to deorbit within five years of ending their missions. (Source: FCC)

The U.S. FCC established a final rule for LEO satellites in large constellations to deorbit within five years of ending their missions. (Source: FCC)

The rule replaced a 25-year deorbit standard and was aimed at mitigating orbital debris and managing an increasingly crowded low Earth orbit. “That’s big,” said FCC Chairwoman Jessica Rosenworcel. The rule change will “mean more accountability and less risk of collisions that increase orbital debris and the likelihood of space communication failures.”

The rule takes effect Sept. 29, 2024. It does not affect satellites deployed before that date and strictly applies to large constellations seeking U.S. market access.

It remains to be seen whether other countries affirm the FCC’s deorbiting regulations. Most spacefaring nations have some form of existing legal framework for space debris mitigation and remediation, though not all.

- The First Commercial Space War

Russia’s invasion of Ukraine in February marked the first extensive use of commercial satellites in a conflict. Commercial operators like Maxar, BlackSky and Planet provided real-time imagery of troop movements and compelling images of the war to both the military and the general public. SpaceX’s Starlink has and continues to be used by the Ukrainian military and civilians for communication.

While commercial satellites have been used in previous conflicts, the onset of what some have called the first commercial space war raises a host of unresolved questions for 2023 and beyond. Chief among them is under what conditions commercial satellites could become legitimate military targets. This dynamic is even further complicated by the fact that the nations providing commercial satellite support to Ukraine (the U.S. and NATO) are not direct combatants.

This satellite image taken Feb. 27, 2022, by Maxar Technologies shows a damaged bridge and road on the approach toward Kyiv. (Source: Maxar Technologies)

This satellite image taken Feb. 27, 2022, by Maxar Technologies shows a damaged bridge and road on the approach toward Kyiv. (Source: Maxar Technologies)

U.S. officials have generally concluded that adversaries will not distinguish between military, civil and commercial satellite systems in a conflict. Some legal experts have argued that commercial space assets could be targeted under the Law of Armed Conflict. However, there are ambiguities around proportionality, collateral damage and environmental damage (such as the effects on the space environment as a result of a kinetic attack).

Military officials continue facing questions about their responsibility to protect commercial space contractors caught in the crossfire. DoD is reportedly in discussions with industry about protections and had considered indemnification in commercial satellite contracts.

- Satellite Cybersecurity

Just as the war in Ukraine elevated discussion about commercial satellite’s role in conflict, it also drew attention to the cyber vulnerabilities of space assets. After the attack on Viasat’s KA-SAT network early this year and numerous attempts to disrupt the Starlink network, head of U.S. Space Force Space Operations Command Lt. Gen. Stephen Whiting acknowledged cyberspace as “the soft underbelly of our global space networks.”

Global events prompted greater attention to cyber vulnerabilities within satellite networks and supply chains. (Source: Pixabay)

Global events prompted greater attention to cyber vulnerabilities within satellite networks and supply chains. (Source: Pixabay)

Over the course of the year, multiple national governments unveiled new standards for vendors to enhance cybersecurity and defend the growing attack surface of connected satellite networks. The U.S. Space Force began rolling out the Infrastructure Asset Pre-Approval Program, establishing new cybersecurity requirements for commercial satcom providers. Germany’s Federal Office for Information Security (BSI) issued new vendor guidance in June, defining baseline cybersecurity requirements throughout the satellite lifecycle, from design, testing and transport to operation and decommissioning.

Industry stakeholders continue advancing cybersecurity best practices to ensure the reliability and continued use of space networks for communication and other critical services. By early 2023, the Space ISAC (Information Sharing and Analysis Center) plans to stand up its Watch Center to help the global space industry monitor threats and enhance preparation for and response to vulnerabilities.

International cybersecurity norms remain underdeveloped and contested. Developments over the last year suggest the importance of space network security, supply chains and ground infrastructure will grow, particularly as national security strategies expand the role of commercial space.

- Space Traffic Management Transition

In 2022, the U.S. DoD began transferring responsibility for civil and commercial space traffic management (STM) to the Department of Commerce. The transition is a key part of maintaining a predictable, safe orbital environment by providing a platform for relevant space situational awareness (SSA) data, collision alerts and support services to operators who would otherwise need a DoD agreement or paid SSA service.

Space traffic management is an important tool to avoid collisions. The U.S. only recently began transferring STM respomnsibilities to a civilian agency. Europe has had civilian Space Surveillance and Tracking system since 2016. (Source: ESA)

Space traffic management is an important tool to avoid collisions. The U.S. only recently began transferring STM respomnsibilities to a civilian agency. Europe has had civilian Space Surveillance and Tracking system since 2016. (Source: ESA)

“The question is should you make safety available only to those who can afford it when the repercussions of a collision in space will be felt by everybody?” Weeden noted. “There’s a strong public good argument for government to have a role in SSA.”

The transition has gotten off to a slow start and will be incremental. Commerce must establish agreements to access DoD data and contracts for commercial data, as well as developing a platform to share information with operators. In December, the Office of Space Commerce (OSC) and DoD announced six organizations will participate in a space traffic data platform pilot project for GEO and MEO. There are hopes that the results of the pilot will be available within the next year and the agencies can move on to solutions for LEO. Challenges coordinating various data sources remain.

Explore More:

Wiper Malware: An Increasing Threat to Satellite and IoT Enabled Capabilities

Podcast: Collision Avoidance Services and Space Domain Awareness

Why DIA Wants More Commercial SDA Partners

Steps Toward Securitizing Commercial Space Networks